Photo by Markus Winkler on Unsplash

🧫 Culture

When we forecast growth it's easy to draw straight lines - up and to the right.

But that's not how it ever actually goes, in practice.

We've talked previously about the hockey stick shape of growth. Next week we'll look a bit closer at the dips that get airbrushed out of these stories. But for today let's think about how we grow a team. In my experience this always happens suddenly rather than smoothly, and it's good if we can anticipate this and have a plan in mind.

I've learned there are several points where early-stage and high-growth teams typically break...

(By which I mean "existing ways of working are no longer suitable, so teams need to either change or fall into dysfunction")

Firstly when the team grows to ~30 people. This is when we start to need an organisational structure for the first time, with reporting lines and job titles and budgets and performance reviews. Which is not to say that we didn't need any of those things previously, but more that they seemed less important when the team was smaller and everybody was mostly on the same page and just doing whatever was needed to keep things moving. This is when, for the first time, we have people in the team we don't talk with directly in the course of a typical week. It starts to get difficult to keep up with what everybody is working on without conscious effort - the ratio of signal-to-noise becomes a problem and we need to start to filter. This is when calendars start to fill up with status meetings. Critically, this is also when the decisions that were made, often unconsciously in the early-days, about team culture and ways of working together start to become embedded, for better or for worse - if the team is not already diverse then it becomes more-or-less impossible to change.

Then, later, things break again when the team grows to ~120 people. This is when it's no longer likely that everybody knows everybody else by name. At this size we need several layers of management - which causes the team to fragment (this could be by function, or by location, or by tenure1) It's much more work to get everybody in the same room, let alone on the same page. This is often when the job of running the team becomes a drag for those who are more suited to early-stages. There is less need for generalists and more need for specialists. This is when it becomes harder to vet every new hire, so inevitably we have to start to deal with performance management. This is also when we start to get real diversity of style - if we want to maintain a shared culture we have to really work at it rather than just assuming that everybody will pick it up by osmosis.

(There are very likely additional breakpoints beyond this size, but I don't have personal experience of those. I'm interested to hear your experiences.)

How do we navigate these break points?

A simple exercise which can help with this is:

Imagine the org chart we'll have when the team is three times as big as it is now.

Draw it on a whiteboard. Don't worry about putting names in each box, or providing detailed job descriptions. Just think about the different functions we'll need in the business when the team has grown to be that big. What are the jobs that will need to be done? In order to answer this we need to think about the shape of the business model that will sustain the team at that point. And possibly also the funding that will be required to get us there2.

Having watched many people struggle with this, I can confidently predict that you'll find this seemingly simple exercise to be anything but simple.

If we have five people now it can be hard to imagine what another ten people might do. How will the current jobs fragment as they increase in complexity and scale? Likewise, if we are a team of 20 people now, imagining the structure when there are 60 in total can be difficult. What sub-teams will form? Who will lead and manage, and how many people will report to each of them?

I've found that two areas that are often overlooked are HR and Finance. In a very small team these are jobs that everybody does, and so nobody does. But as the team grows these become separate functions, and are actually vital to fuelling the growth itself.

Another common point of tension is the split between product and marketing/sales, and within the product team the split between engineering and operations. Again, in a smaller team these are functions that are typically shared between multiple people where everybody does a bit of everything, but as the team grows these will become areas with assigned responsibilities and how those interact becomes critical.

Once we've drawn the boxes we can start to think about the existing people we have in the team today and how they might fit into that future structure. Where are the gaps? Where do people need to evolve their role or start to specialise? Who will be excited about being part of the team at that size and who will likely want to move on at that point?

If that wasn't too hard, then do it again, but this time imagine the team when it is five times as big as it is now! This will highlight a whole new layer of complexity.

One of the mistakes we often make when thinking about startups is imagining them to have a steady state. It's not that they one day change. It's that they are constantly changing. This can be invigorating but also exhausting. We have to repeatedly break things to fix them. But, if we can always be thinking a few moves ahead then we can keep up with the adaption that is required to ensure that we get to the next level. And then to the one beyond that.

📍Plot

It's easy to have a lofty end goal in mind. It's better to have a rough map showing how we currently think we will get there3. It's surprising how often teams have the goal but not the route.

To plot a path, the questions we need to answer are:

What are the intermediate milestones?

What are the things we need to do, have and be?

How will we know we're on track?

If you are a visual person then you might like to represent this as an actual map - i.e. draw a diagram that represents the different elements.

If you are a numbers person then you might prefer a spreadsheet that shows the different metrics that will be important and how they interact with each other.

If you are a storyteller then you probably prefer a keynote format, where you can share a narrative that will inspire and excite others.

All of these can work. The important thing is to be able to communicate this plan to everybody who will work together to make it happen: the current team, investors and other stakeholders, and not least to the customers who will ultimately fund it.

How We Win

Perhaps the most famous recent example of a “How We Win” plan is the Secret Tesla Motors Master Plan shared by Elon Musk in 2006, long before the company was synonymous with electric vehicles:

Build sports car

Use that money to build an affordable car

Use that money to build an even more affordable car

While doing above, also provide zero emission electric power generation options

This is more-or-less exactly what they have done4. Hindsight makes it all look obvious!

We wrote something similar for Vend, on a flight back from San Francisco in 2012. Vaughan (the founder and then-CEO) and I had spent the previous week pitching to potential investors. Reflecting on the feedback we'd got, we had a much tighter understanding of the things we would need to demonstrate in order to raise more capital and ultimately grow the business. We cobbled together a very rough presentation that explained this as simply as we could.

It broke our strategy down into four streams5:

Build a great team

Build a great product

Develop low-touch sales channels

Manage cash

Still jet lagged, we presented a version of it to the small team back in Auckland. The intention was that everybody in the team would be able to identify their specific part of that broader plan, and be clear about what they needed to do in order to contribute to the overall success. The story was simple: if we do those four things we believe we will win!

Later this became a company tradition. As it was repeated over the years it was refined and polished. Some former Venders may fondly remember the versions that Angus (the CFO at the time) would do for everybody as part of the on-boarding of new team members.

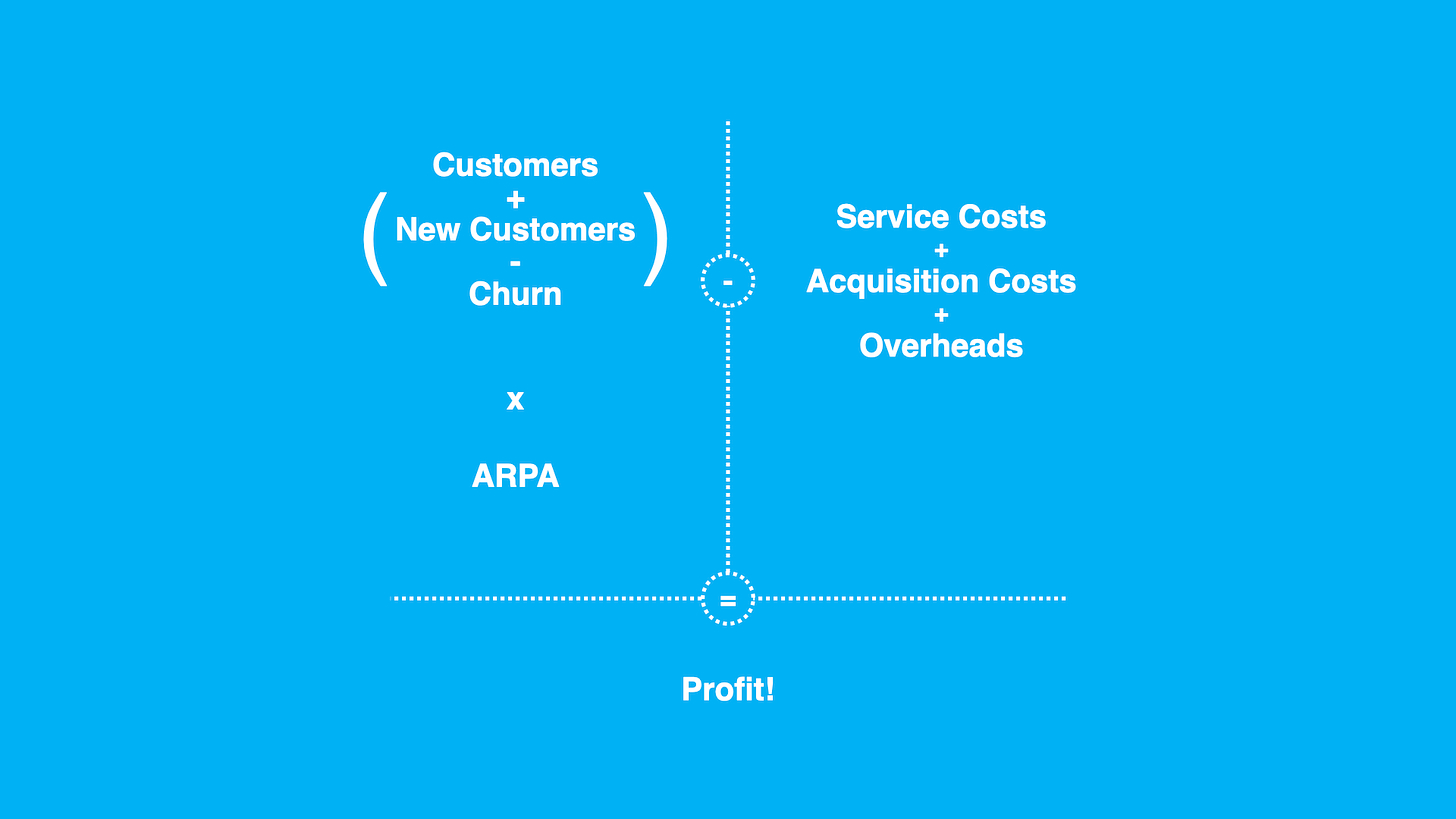

In 2017 I presented something similar to the Timely team, and included this diagram:

This is just the standard business model6:

Revenue - Expenses = Profit

With some SaaS specific elements added to provide detail:

Revenue = Customers (Net of Churn) * Average Revenue Per Account

Expenses = Service Costs (CTS or COGS) + Acquisition Costs (CAC) + Overheads

This breakdown let us think about each of these elements separately:

How do we increase the number of new customers?

How do we increase retention or decrease churn?

How do we increase the average revenue per account?

How do we decrease the average amount it costs to service each customer?

How do we decrease how much it costs to acquire a new customer?

How do we reduce overheads?

This is not an especially exciting list of questions. All of those things are difficult problems to solve. None of them is glamorous (did I mention: successful execution in a startup is much more hard grind than magic spark). But these are the things that matter, in the end.

This list also highlights the trade-offs. It’s impossible to "win" on all of those dimensions. They impact each other - e.g. growing the customer support team to try and reduce churn increases the service costs and overheads. We have to pick our battles, and focus on the bits that we think are most critical to our particular success or the areas where we think we can actually influence the outcomes. We need to find the things that can be measured or described that contribute to that result.

In the long run we win by making something so great that people will pay more for it than it costs us to make

By the way, this divide and conquer approach even works for things completely unrelated to startups.

For example, many years ago I set myself the goal of running a half-marathon in 1h 45m, which requires an average pace just under 5mins/km. Understanding that my strength is a high pain tolerance, and realising that whatever happened I was likely to be fading by the end, I decided to go with this simple plan:

4:46/km to 12km

5:15/km to finish

In other words, go out fast and hang on!

The intermediate milestone was 12km in ~57 minutes. I decided not to worry about the second half of the race. I realised that the first half was critical - if I wasn’t on track then I didn’t have a hope. Even though I hadn't run the full 21km distance much in training, I'd done that shorter distance at the required pace, so I knew that was possible. On the day I got there in 56m 16s, which was lucky because my planning hadn't accounted for the increasing northerly we had to run into on the way back (one of the consistent joys of running in Wellington!)

I was delighted to cross the finish line in 1h 44m 10s. 😅

It's amazing and depressing how often the things that our teams focus on are not correlated at all with how we win. We get distracted by growth rates (forgetting that things that grow really quickly - like cancer - can actually kill us). We get distracted by the size of our team, or the amount of capital we've raised (both vanity metrics). We get distracted by winning awards. We forget that we need to apply our own mask first, before helping others.

But, those companies that we read about, after they have achieved great outcomes, are the ones who manage to put these distractions aside and execute a plan that keeps focus on the things that actually matter.

How well does your team understand your plan to win?

When was the last time you wrote it down or said it out loud?

🪙 Toss

This week was the conclusion of the T20 Cricket World Cup.

The final was Australia vs New Zealand, with the Australians completing a comfortable victory in the final.

Afterwards, there was some discussion about the impact of the coin toss on the outcome of the tournament, so I thought it would be interesting to do some analysis.

It was a drawn-out tournament, with multiple stages, but in the end there were basically six teams that were competing for the title. On one side of the draw South Africa, Australia and England, who beat all other teams except for each other. And likewise on the other side, with New Zealand, Pakistan and India.

So let's consider the nine matches played between these six top teams...

In each case the team batting first is listed first, the team chasing is listed second, the winner is in bold and the * marks which team won the coin toss.

SAF vs AUS (*)

IND vs PAK (*)

NZL vs PAK (*)

AUS vs ENG (*)

IND vs NZL (*)

SAF vs ENG (*)

ENG vs NZL (*) (semi-final)

PAK vs AUS (*) (semi-final)

NZL vs AUS (*) (final)

Can you see the obvious pattern?

Almost every match was won by the team that batted second, which was also the team that won the toss.

The only exception was the pool match between South Africa and England where South Africa won despite losing the toss and batting first. They scored 189, including 94 not out from Rassie van der Dussen. English opener Jason Roy was injured and retired hurt during their chase, where they still made 179 batting second.

I like to say that the reason I get up at 2am to watch sport live is because that's the only way to influence the result. But in this case it's difficult not to feel that an alarm set to only go off if we won the toss might have made more sense.

Anyway, congratulations to Aaron Finch on winning the toss in the final. I think given other cricket news this week we can at least confidently say that Australian captains are great tossers.

Top Three is a weekly collection of things I notice in 2021. I’m writing it for myself, and will include a lot of half-formed work-in-progress, but please feel free to follow along and share it if it’s interesting to you.

The strongest signal of this fracturing is teams that refer to "the business", as if they are not themselves part of the business!

This exercise is actually a great way to tease out the unit of progress to discuss with potential investors.

The "currently" is important - goals can be consistent, but plans need to be flexible to change, based on what we learn from the experiments we've completed so far.

In 2016 he published an updated version of this called Master Plan, Part Deux (obviously no longer secret!) If these plans run on a ten-year cadence then they are now halfway through that updated plan. Those people who were brave enough to invest in 2016 have seen the stock price increase by 2,700%+ since then. So, it's going okay so far, I guess.

Three of these headings might ring some bells for those who remember the “three engines” we talked about a few weeks ago. The fourth is the ticket to the game.

See also The Size of Your Truck