Photo by blueberry Maki on Unsplash

🔮 Predict

When you hear people explaining their vision for the future, always consider if it's thematic or specific.

A thematic vision is a top-down way of thinking and describes general trends. A specific vision is a bottom-up way of thinking and describes individual ventures or projects.

A theme without a specific venture is academic. A venture or project without a supporting theme is likely to face headwinds.

The best ideas are a combination of the two: a specific venture that is created to capitalise on a general trend.

Some examples:

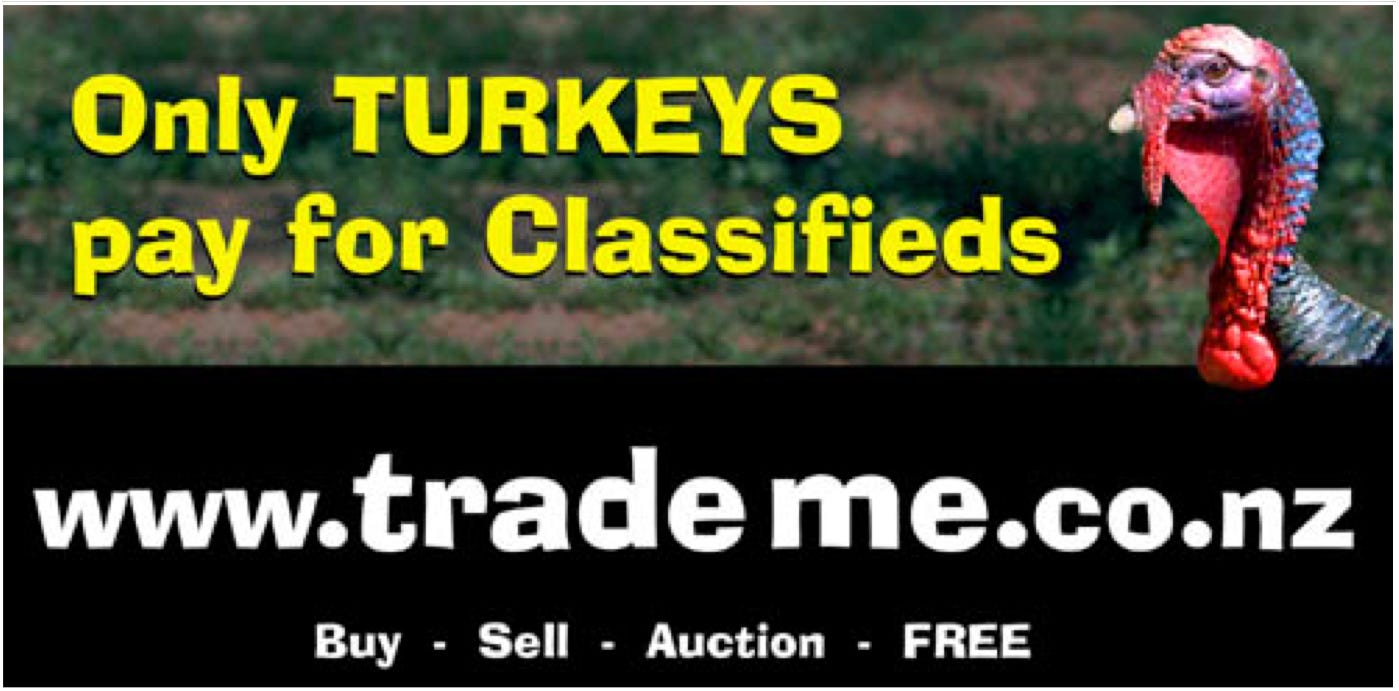

For Trade Me the general trend was the web as a consumer platform, the specific idea was to replace the newspaper classifieds by taking advantage of the benefits of the web (e.g. longer descriptions, photos) and to create a network effect that kept marketing costs very low.

For Xero the general trend was the shift to Software-as-a-Service (SaaS), the specific idea was accounting software for small businesses, using accountants and advisers as the sales channel.

What's next?

Be general and specific!

⏭ Skip

History isn’t fact. It’s narrative.

I sometimes feel sorry for journalists, who only ever get to write about tiny slivers of the lifecycle of a startup - a new company is founded; then there are new investors; the product is launched; then the company is sold.1

Those are all great days, if and when they happen. But they are the rare exceptions.

I've had the opportunity to work on startups that have been incredibly successful and have ticked off all of these milestones. But by far and away the most interesting parts of all of them are the times when there were significant stumbles or backwards steps.

Unfortunately those stories are often entirely brushed over in the popular mythology.

When I think about Trade Me, Xero, Vend and Timely, one of the few things all four companies have in common is that they all had significant near-death moments...

2001

Trade Me was only two years old and still quite fragile. In just 18 months we had grown from 10,000 members to over 100,000 members. That was exhilarating. But the original business model (free online classifieds, supported by advertising2) had failed to generate any significant revenue. We'd spent all of the cash, and new investors were seemingly uninterested in giving us any more. The company was being propped up by loans from existing shareholders.

I had only recently become a shareholder myself, after Trade Me acquired my own startup, Flathunt. I didn't have any cash to lend, but I did work for several months at a significantly reduced salary, before that became unsustainable. I resigned and moved overseas. If I'm honest, I didn't expect there would be anything to come back to at that point.

Actually, three out of the four people from the original team all left, including the founder, Sam Morgan and his sister Jessi, who was the first employee before me. At one point, all three of us were living and working as contractors in London, leaving Nigel Stanford running things more-or-less by himself back in New Zealand. That period of time has never been properly documented. Partly because it doesn't really fit the arc of "up and to the right".

One of the last changes I was asked to make to the website before leaving was to implement success fees. It wasn't so much that we realised this was the golden ticket - more that we'd run out of other options, so had nothing to lose from giving it a try. Eventually this would become an amazing business model that would fuel a very successful company.

Sam, Jessi and I all later returned to executive roles in the business. In 2006 the company was sold to Fairfax for $750m.

Let's not pretend that outcome was obvious at the time.

2008/2009

Some people, especially those in Australia, think that the Xero story started around the time of the listing on the ASX at the end of 2012. The share price then was A$4.65, and by early 2014 it had jumped to over A$45.

But there is a long pre-history prior to those glory days, where the market performance wasn't nearly as good and the outcome for the company was much more unproven.

Xero was listed on the NZX in 2007. The IPO, which valued the company at $50m, raised $15m of new capital at $1 per share. For several years after that the share price was below this listing price. Despite the global ambitions, there was pretty modest customer traction, more-or-less entirely in New Zealand.

The IPO prospectus forecast that the company would have 1,300 subscribers by May 2008 (12 months after the listing).3 The actual result was 1,408. Although as this graph from the Annual Report shows, a good percentage of those signed up in the final few weeks of the reporting period.

Source: Xero Annual Report, May 2008

The total subscription revenue for that year was just $134k. The company actually made more money from interest on the unspent IPO funds. It was an anxious time!

The company was burning through cash too quickly. It wasn't obvious that the market would be patient long enough. There was a suggestion that it could be the first public company to be named after its share price. There was a high turnover of senior staff during this time, especially sales and marketing related roles. I was one of those who left. (Thankfully, I didn’t table flip completely and sell my shares!)

In 2009 the company raised NZ$23m of new capital from MYOB founder Craig Winkler.4 It's mostly forgotten now but the price on the new shares issued in that round was 90c (i.e. below the IPO price from two years earlier) and after that investment he owned 24% of the company.

With the benefit of hindsight that was a turning point. Within the next three years Xero raised a further $170m from various investors, the number of subscribers increased from 6,000 to 78,000 and revenue increased 20x. Now it has millions of subscribers.

Let's not pretend that outcome was obvious at the time.

2015

Vend was growing at an eye-watering pace, but also burning significant amounts of cash. By the end of that year we came very close to shutting the company down.

We had signed a term sheet with a new investor who then changed their mind at the last minute. This left us with some hard decisions to make urgently.

We were default dead. We had willingly signed up to a growth path that required us to get permission to continue to exist from investors every 18-24 months, and in this round time had suddenly run out.

When this all unfolded I was in Berlin, with Barry Brott (who was also an investor and director). The intention was to meet some of the new team we had recently hired there. Instead we spent the day working through the process of telling that same team we would need to shut the office.

We spent that night on a series of urgent phone calls with existing investors, trying to raise further funding. Not surprisingly, there were a range of reactions to that request. I got some very direct feedback on my performance! Trying to find consensus in that environment was tricky.

By the time we finished all of this it was the middle of the night. We decided to head out for some food, and for our sins got flashed by a drunk German in the elevator. I was too exhausted to do anything other than laugh.

I flew straight from Berlin to Auckland where there were a number of further difficult decisions and hard conversations waiting. We had to urgently reduce the team size, and make a number of people redundant. That was painful - those people had believed in what we were trying to build and done the hard yards to contribute to that. And I acknowledge I was on the easy end of all of those conversations.

However, a few weeks later we came out the other side of that with new funding confirmed and a plan forwards for the team. Within a few months there was almost an entirely new board (Barry was the only survivor) and executive team (Alex Fala, who we had recently hired in a strategy role took over first as CFO then as CEO) and the business continued.

Earlier this year Vend was acquired by Lightspeed, one of our fiercest competitors from back in those days, for $485m.

Let's not pretend that outcome was obvious at the time.

2020

A much more recent story (so much so that it almost feels too soon to tell it)...

Timely was nearly one of the first victims of the COVID pandemic. As the virus started to spread around the world, the vast majority of our customers (hairdressers, beauty salons, spas etc) were suddenly shut. We kept a close eye on the impact on subscription revenue, and it wasn't pretty. We had no idea how much longer this would continue, but the graph trended pretty quickly to zero.

This was a moment that required remarkable leadership. CEO Ryan Baker, who with his executive team had spent the last few years building an awesome team, committed to preserving every job. We offered generous discounts to customers. We immediately cut board fees and made deep cuts to executive salaries, and then asked the team what they could do to help. He described the approach as: "all of us will be affected a little so that none of us had to be affected a lot". Overall we reduced costs by 20%. Some staff agreed to do more so that others, who would be more heavily impacted, could do less. It was an amazing collective response.

This created a positive feedback loop. With job security, the whole team was focussed on helping customers navigate the lock downs, providing whatever support we could. This helped us retain the bulk of our customer base, albeit on reduced subscriptions. Because many competitors were missing-in-action during this time we actually managed to gain market share. That revenue allowed us to keep the cycle going.

Remarkably within a few months we able to repay staff the amounts that had been cut. And shortly after that we started the conversations that would eventually lead to the sale to EverCommerce (one of the terms of that sale was that the wage subsidy we'd received from the NZ government was also repaid, which was a nice full stop to this phase).

Let's not pretend that outcome was obvious at the time!

When a startup is a big success it's really easy to focus on the end point, and forget about the route. When the stories are re-told over and over, details get re-written or forgotten. And the bits that are omitted and updated are nearly always these dips.

That's a shame, because it obscures the lessons people can learn from those hard moments. Those who are just starting out on their own venture don't always anticipate that it might happen to them. The biggest deceit is thinking that it won't.

For me, there are some very negative personal memories attached to each of those stories. Amazingly, they all had happy endings.

People sometimes describe working on a startup as “a rollercoaster”. I think that's the wrong metaphor, for lots of reasons, but specifically in this case because every theme-park ride ends where it started. That's very seldom true of growth-stage businesses in my experience. You get exposed to so much in such a short period of time, that when you come out the other end you're a very different person.

These dips are the moments of truth for investors too. It's easy to be an investor in a company that only goes well. When things go badly we get to separate those who are really helpful from those who are along for the ride. Normally these are expensive lessons for those who are prepared to step up. But also the most rewarding, in both senses of that word, when it works out.

It doesn't always.

⛑ Triage

This week we got to launch a new thing we’ve been building, which is always exciting and terrifying in equal measure.

I’m delighted to say Triage 2 available now on the App Store. 😍

It’s once again the first app I open every morning. Swiping through a literal stack of emails is the most satisfying way to quickly tame an inbox.

The original Triage was released in 2013 and became a best-selling paid app on the App Store charts (around the same time as Lorde was top of the Billboard charts).

Triage 2 has been completely rebuilt by Nik Wakelin using the latest tools and frameworks. The fresh new design is by Isaac Minogue.

As always when building software, the real treasure is the new friends we made along the way: Swift, SwiftUI, the Gmail API & iCloud. And not forgetting our oldest and dearest IMAP.

(Honestly, the more you learn about email “standards” the more you become curious about how anything in the world that depends on these works at all!)

Triage 2 has a brand new business model too - it’s completely free to download and use. There is a small annual subscription for those who want to use multiple accounts and other advanced features.

So, it costs you nothing to give it a try today. And please tell your friends!

Top Three is a weekly collection of things I notice in 2021. I’m writing it for myself, and will include a lot of half-formed work-in-progress, but please feel free to follow along and share it if it’s interesting to you.

This was really highlighted to me when I watched The Social Network movie about the early stages of Facebook. In one scene they are a small team struggling away in a house in Palo Alto, and nobody has heard of them. Then, it jumps quickly to them moving into their first office and celebrating 1,000,000 users. As if that just happened while they weren't looking! I couldn't help but feel like they just skipped over all of the most interesting bits in the story, in a montage.

The prospectus also estimated that the APRU would be $75 (actually it’s been consistently between $25 and $30 ever since), and contained this wonderful underestimate:

“Dependent on pricing, the Directors assess, based on their current estimates of Xero’s cost base, that Xero’s New Zealand revenue will begin to exceed its New Zealand cost base at around 8,000 customers. However, Xero will also be investing in the development and growth of the business and pursuing expansion of the business into the UK and Australia. Therefore, the Directors do not currently expect that Xero will record an overall profit for at least three years.”

Craig had quit as CEO at MYOB a year prior to that after shareholders at MYOB had blocked his share option grant.